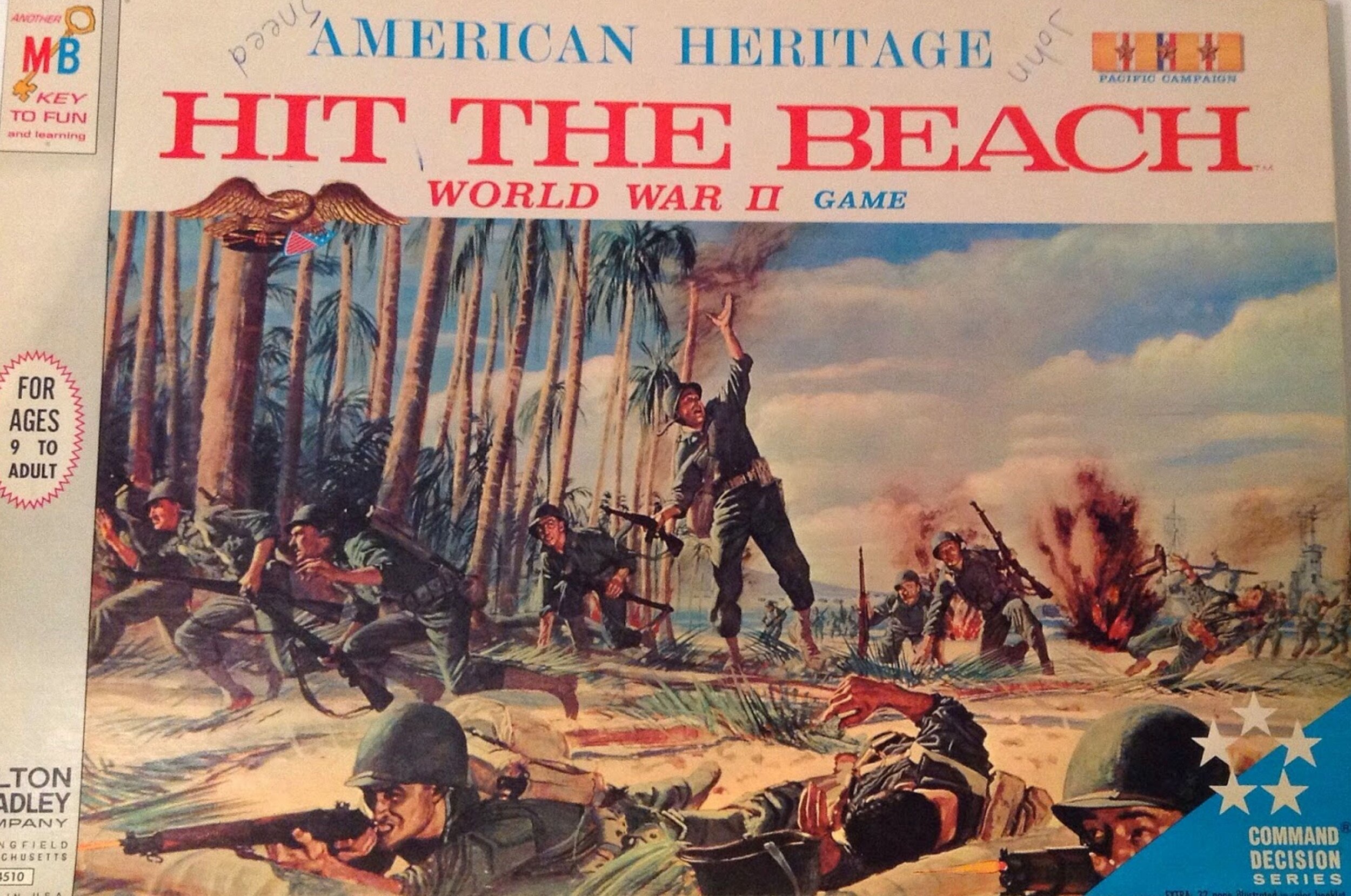

During the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Milton-Bradley Company created a number of games based on American wars. Broadside was derived from the War of 1812, Battle Cry from the Civil War, Dogfight from World War I and Hit the Beach from World War II. Whenever one of those games appeared on the shelves of Marlowe’s Department Store on Main Street, I would get some of the money from my Manchester Evening Herald paper route and go buy it.

As I look back on those games now from the perspective of more than a half century, I am struck by this emphasis on war in the games I played when I was a kid. Those days weren’t all that far removed from WWII, but since I was born four years after the war ended, they meant no more to me personally than the American Revolution. I remember watching a television program in 1964 when Walter Cronkite walked along Omaha Beach in Normandy, France with Dwight Eisenhower as they recounted the events that took place there twenty years before. As far as I was concerned these two men were describing ancient history. I didn’t realize it at the time, but for many of the grownups working in stores on Main Street, teaching in my classrooms or singing in my church’s choir, the Second World War was still quite real, as real as 9/11 is for me now as its 20th anniversary draws near. I can more fully appreciate how much our society still lived in the shadow of World War Two when I was playing Hit the Beach.

On top of the lingering effects of World War Two on our society, 1961-1965 was also the centennial of the Civil War. My friend’s father built a large platform in the attic of their house and Craig would spend hours designing battlefields on it using hundreds of toy Civil War soldiers along with toy trees and houses. When I came over to see him, we would admire all that he had done in the past week, then play at strategically fighting a battle with the soldiers. Craig would usually win because he had set up the battle giving the advantage to the Rebel army that he always commanded, but I didn’t really mind because of the fun we would have for the hour or so it would take for the battle to be won or lost.

I suppose it's a little surprising that someone who made a game out of war as much as I once did would end up never firing a gun other than an air rifle or a cap pistol. I not only played war games, I would sometimes neglect my homework when I went to Mary Cheney Library to get a book on World War Two and read it until closing time. But in the years that followed, I came to realize that war is not a game. About a year ago, I was looking at some old pictures of Manchester. One of them was of a company of soldiers marching up Main Street in their uniforms, rifles over their shoulders, all looking forward with determined looks. It was 1917 or 1918 and they were heading toward a train in the north end of town for the first step in the journey that would eventually take them to France. I didn’t see any of the glory of war in that picture I would have perceived 60 years ago. Instead, my eyes misted with tears.

David James Madden